Linear discriminant analysis, explained

02 Oct 2019Intuitions, illustrations, and maths: How it’s more than a dimension reduction tool and why it’s robust for real-world applications.

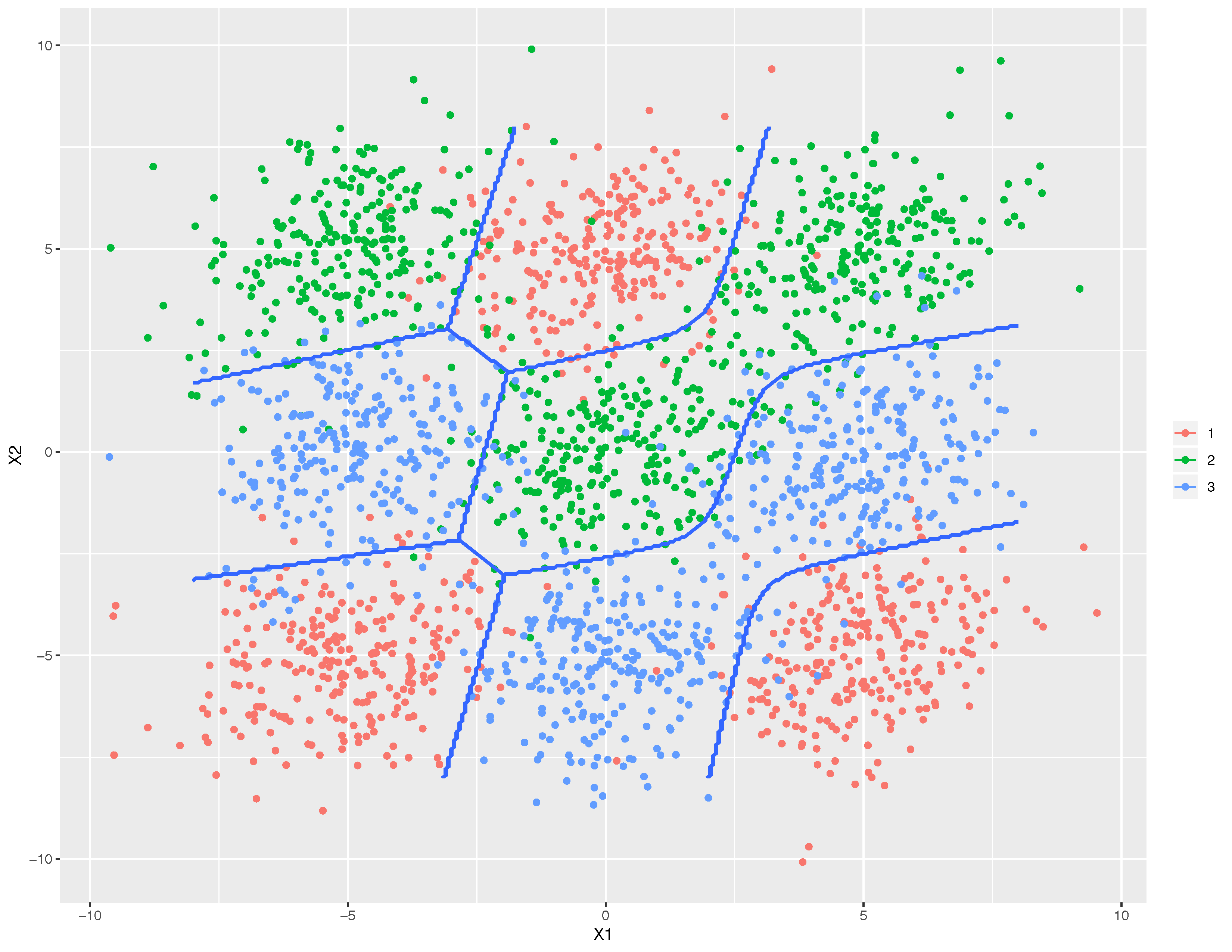

This graph shows that boundaries (blue lines) learned by mixture discriminant analysis (MDA) successfully separate three mingled classes. MDA is one of the powerful extensions of LDA.

This graph shows that boundaries (blue lines) learned by mixture discriminant analysis (MDA) successfully separate three mingled classes. MDA is one of the powerful extensions of LDA.

Key takeaways

- Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) is not just a dimension reduction tool, but also a robust classification method.

- With or without data normality assumption, we can arrive at the same LDA features, which explains its robustness.

Introduction

LDA is used as a tool for classification, dimension reduction, and data visualization. It has been around for quite some time now. Despite its simplicity, LDA often produces robust, decent, and interpretable classification results. When tackling real-world classification problems, LDA is often the first and benchmarking method before other more complicated and flexible ones are employed.

Two prominent examples of using LDA (and it’s variants) include:

- Bankruptcy prediction: Edward Altman’s 1968 model predicts the probability of company bankruptcy using trained LDA coefficients. The accuracy is said to be between 80% and 90%, evaluated over 31 years of data.

- Facial recognition: While features learned from Principal Component Analysis (PCA) are called Eigenfaces, those learned from LDA are called Fisherfaces, named after the statistician, Sir Ronald Fisher. We explain this connection later.

This article starts by introducing the classic LDA and why it’s deeply rooted as a classification method. Next, we see the inherent dimension reduction in this method and how it leads to the reduced-rank LDA. After that, we see how Fisher masterfully arrived at the same algorithm, without assuming anything on the data. A hand-written digits classification problem is used to illustrate the performance of the LDA. The merits and disadvantages of the method are summarized in the end.

The second article following this generalizes LDA to handle more complex problems. By the way, you can find a set of corresponding slides where I present roughly the same materials written in this article.

Classification by discriminant analysis

Let’s see how LDA can be derived as a supervised classification method. Consider a generic classification problem: A random variable $X$ comes from one of $K$ classes, with density $f_k(\mathbf{x})$ on $\mathbb{R}^p$. A discriminant rule tries to divide the data space into $K$ disjoint regions $\mathbb{R}_1, \dots, \mathbb{R}_K$ that represent all classes (imagine the boxes on a chessboard). With these regions, classification by discriminant analysis simply means that we allocate $\mathbf{x }$ to class $j$ if $\mathbf{x}$ is in region $j$. The question is then, how do we know which region the data $\mathbf{x }$ falls in? Naturally, We can follow two allocation rules:

- Maximum likelihood rule: If we assume that each class could occur with equal probability, then allocate $\mathbf{x }$ to class $j$ if $j = \arg\max_i f_i(\mathbf{x})$.

- Bayesian rule: If we know the class prior probabilities, $\pi_1, \dots, \pi_K$, then allocate $\mathbf{x }$ to class $j$ if $j = \arg\max_i \pi_i f_i(\mathbf{x}) $.

Linear and quadratic discriminant analysis

If we assume data comes from multivariate Gaussian distribution, i.e. $X \sim N(\mathbf{\mu}, \mathbf{\Sigma})$, explicit forms of the above allocation rules can be obtained. Following the Bayesian rule, we classify $\mathbf{x}$ to class $j$ if $j = \arg\max_i \delta_i(\mathbf{x})$ where

\[\begin{align} \delta_i(\mathbf{x}) = \log f_i(\mathbf{x}) + \log \pi_i \end{align}\]is called the discriminant function. Note the use of log-likelihood here. The decision boundary separating any two classes, $k$ and $\ell$, is the set of $\mathbf{x}$ where two discriminant functions have the same value, i.e. \(\{\mathbf{x}: \delta_k(\mathbf{x}) = \delta_{\ell}(\mathbf{x})\}\). Therefore, any data that falls on the decision boundary is equally likely from the two classes.

LDA arises in the case where we assume equal covariance among $K$ classes, i.e. $\mathbf{\Sigma}_1 = \mathbf{\Sigma}_2 = \dots = \mathbf{\Sigma}_K$. Then we can obtain the following discriminant function:

\(\begin{align} \delta_{k}(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{x}^{T} \mathbf{\Sigma}^{-1} \mathbf{\mu}_{k}-\frac{1}{2} \mathbf{\mu}_{k}^{T} \mathbf{\Sigma}^{-1} \mathbf{\mu}_{k}+\log \pi_{k} \,, \label{eqn_lda} \end{align}\) using the Gaussian distribution likelihood function.

This is a linear function in $\mathbf{x}$. Thus, the decision boundary between any pair of classes is also a linear function in $\mathbf{x}$, the reason for its name: linear discriminant analysis. Without the equal covariance assumption, the quadratic term in the likelihood does not cancel out, hence the resulting discriminant function is a quadratic function in $\mathbf{x}$: \(\begin{align} \delta_{k}(\mathbf{x}) = - \frac{1}{2} \log|\mathbf{\Sigma}_k| - \frac{1}{2} (\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{\mu}_{k})^{T} \mathbf{\Sigma}_k^{-1} (\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{\mu}_{k}) + \log \pi_{k} \,. \label{eqn_qda} \end{align}\)

Similarly, the decision boundary is quadratic in $\mathbf{x}$. This is known as quadratic discriminant analysis (QDA).

Which is better? LDA or QDA?

In real problems, population parameters are usually unknown and estimated from training data as $\hat{\pi}_k, \hat{\mathbf{\mu}}_k, \hat{\mathbf{\Sigma}}_k$. While QDA accommodates more flexible decision boundaries compared to LDA, the number of parameters needed to be estimated also increases faster than that of LDA. From (\ref{eqn_lda}), $p+1$ parameters (nonlinear transformation of the original distribution parameters) are needed to construct the discriminant function. For a problem with $K$ classes, we would only need $K-1$ such discriminant functions by arbitrarily choosing one class to be the base class, i.e.

\[\delta_{k}'(\mathbf{x}) = \delta_{k}(\mathbf{x}) - \delta_{K}(\mathbf{x})\,,\]for $k = 1, \dots, K-1$. Hence, the total number of estimated parameters for LDA is \((K-1)(p+1)\).

On the other hand, for each QDA discriminant function (\ref{eqn_qda}), mean vector, covariance matrix, and class prior need to be estimated:

- Mean: $p$

- Covariance: $p(p+1)/2$

- Class prior: 1

The total number of estimated parameters for QDA is \((K-1)\{p(p+3)/2+1\}\).

Therefore, the number of parameters estimated in LDA increases linearly with $p$ while that of QDA increases quadratically with $p$. We would expect QDA to have worse performance than LDA when the dimension $p$ is large.

Best of two worlds? Compromise between LDA & QDA

We can find a compromise between LDA and QDA by regularizing the individual class covariance matrices. Regularization means that we put a certain restriction on the estimated parameters. In this case, we require that individual covariance matrix shrinks toward a common pooled covariance matrix through a penalty parameter $\alpha$:

\[\hat{\mathbf{\Sigma}}_k (\alpha) = \alpha \hat{\mathbf{\Sigma}}_k + (1-\alpha) \hat{\mathbf{\Sigma}} \,.\]The pooled covariance matrix can also be regularized toward an identity matrix through a penalty parameter $\beta$:

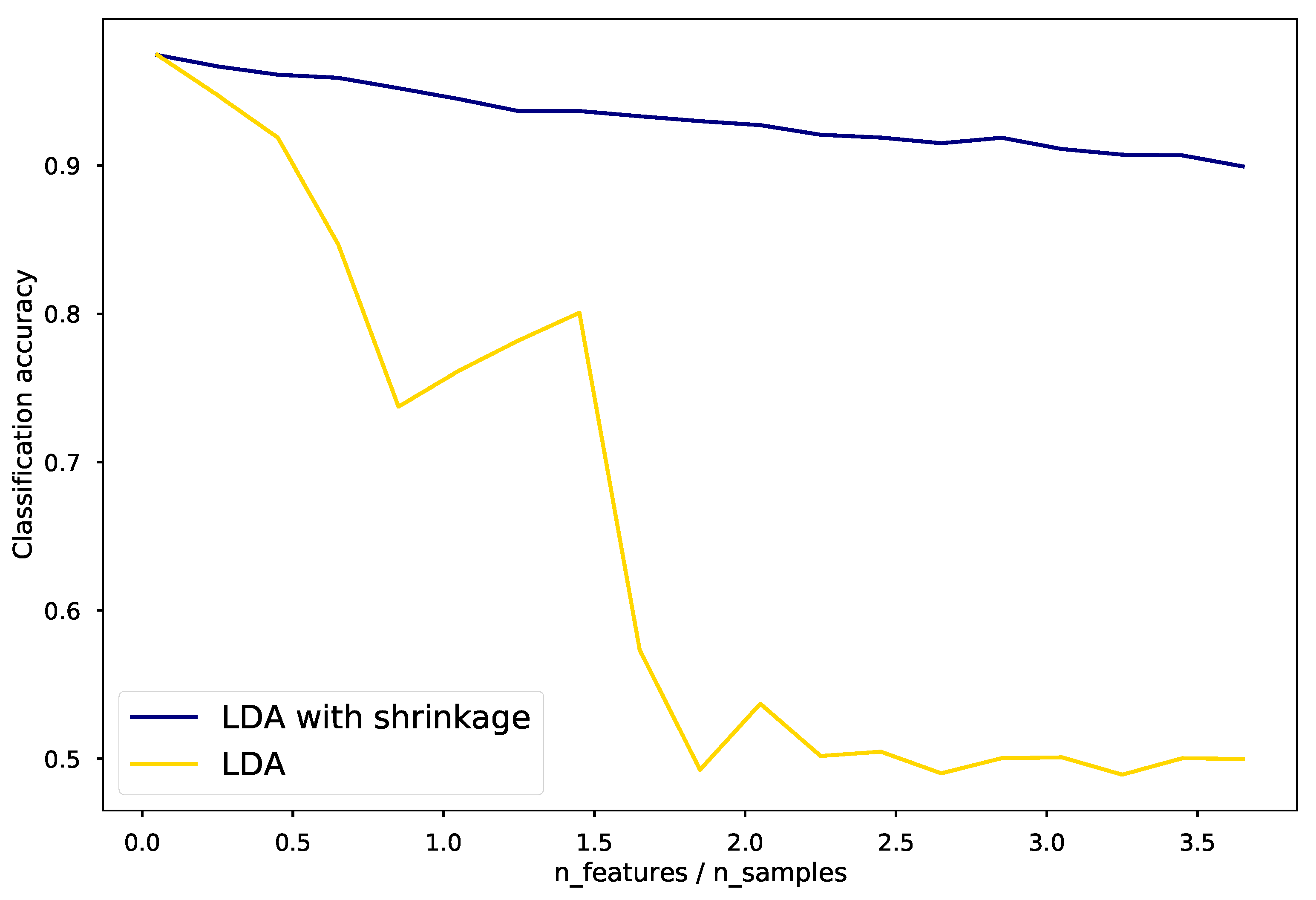

\[\hat{\mathbf{\Sigma}} (\beta) = \beta \hat{\mathbf{\Sigma}} + (1-\beta) \mathbf{I} \,.\]In situations where the number of input variables greatly exceeds the number of samples, the covariance matrix can be poorly estimated. Shrinkage can hopefully improve estimation and classification accuracy. This is illustrated by the figure below.

Click here for the script to generate the above plot, credit to scikit-learn.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import make_blobs

from sklearn.discriminant_analysis import LinearDiscriminantAnalysis

%matplotlib inline

n_train = 20 # samples for training

n_test = 200 # samples for testing

n_averages = 50 # how often to repeat classification

n_features_max = 75 # maximum number of features

step = 4 # step size for the calculation

def generate_data(n_samples, n_features):

"""Generate random blob-ish data with noisy features.

This returns an array of input data with shape `(n_samples, n_features)`

and an array of `n_samples` target labels.

Only one feature contains discriminative information, the other features

contain only noise.

"""

X, y = make_blobs(n_samples=n_samples, n_features=1, centers=[[-2], [2]])

# add non-discriminative features

if n_features > 1:

X = np.hstack([X, np.random.randn(n_samples, n_features - 1)])

return X, y

acc_clf1, acc_clf2 = [], []

n_features_range = range(1, n_features_max + 1, step)

for n_features in n_features_range:

score_clf1, score_clf2 = 0, 0

for _ in range(n_averages):

X, y = generate_data(n_train, n_features)

clf1 = LinearDiscriminantAnalysis(solver='lsqr', shrinkage=0.5).fit(X, y)

clf2 = LinearDiscriminantAnalysis(solver='lsqr', shrinkage=None).fit(X, y)

X, y = generate_data(n_test, n_features)

score_clf1 += clf1.score(X, y)

score_clf2 += clf2.score(X, y)

acc_clf1.append(score_clf1 / n_averages)

acc_clf2.append(score_clf2 / n_averages)

features_samples_ratio = np.array(n_features_range) / n_train

with plt.style.context('seaborn-talk'):

plt.plot(features_samples_ratio, acc_clf1, linewidth=2,

label="LDA with shrinkage", color='navy')

plt.plot(features_samples_ratio, acc_clf2, linewidth=2,

label="LDA", color='gold')

plt.xlabel('n_features / n_samples')

plt.ylabel('Classification accuracy')

plt.legend(prop={'size': 18})

plt.tight_layout()

Computation for LDA

We can see from (\ref{eqn_lda}) and (\ref{eqn_qda}) that computations of discriminant functions can be simplified if we diagonalize the covariance matrices first. That is, data are transformed to have an identity covariance matrix (no correlation, variance of 1). In the case of LDA, here’s how we proceed with the computation:

- Perform eigen-decompostion on the pooled covariance matrix: \(\hat{\mathbf{\Sigma}} = \mathbf{U}\mathbf{D}\mathbf{U}^{T} \,.\)

- Sphere the data: \(\mathbf{X}^{*} \leftarrow \mathbf{D}^{-\frac{1}{2}} \mathbf{U}^{T} \mathbf{X} \,.\)

- Obtain class means in the transformed space: \(\hat{\mu}_1, \dots, \hat{\mu}_{K}\).

- Classify $\mathbf{x}$ according to $\delta_{k}(\mathbf{x}^{*})$:

Step 2 spheres the data to produce an identity covariance matrix in the transformed space. Step 4 is obtained by following (\ref{eqn_lda}). Let’s take a two-class example to see what LDA is doing. Suppose there are two classes, $k$ and $\ell$. We classify $\mathbf{x}$ to class $k$ if

\[\begin{align} \delta_{k}(\mathbf{x}^{*}) - \delta_{\ell}(\mathbf{x}^{*}) > 0. \end{align}\]Following the four steps outlined above, we write

\[\begin{align*} \delta_{k}(\mathbf{x}^{*}) - \delta_{\ell}(\mathbf{x}^{*}) &= \mathbf{x^{*}}^{T} \hat{\mu}_{k}-\frac{1}{2} \hat{\mu}_{k}^{T} \hat{\mu}_{k}+\log \hat{\pi}_{k} - \mathbf{x^{*}}^{T} \hat{\mu}_{\ell} + \frac{1}{2} \hat{\mu}_{\ell}^{T} \hat{\mu}_{\ell} - \log \hat{\pi}_{k} \\ &= \mathbf{x^{*}}^{T} (\hat{\mu}_{k} - \hat{\mu}_{\ell}) - \frac{1}{2} (\hat{\mu}_{k}^{T}\hat{\mu}_{k} - \hat{\mu}_{\ell}^{T} \hat{\mu}_{\ell}) + \log \hat{\pi}_{k}/\hat{\pi}_{\ell} \\ &= \mathbf{x^{*}}^{T} (\hat{\mu}_{k} - \hat{\mu}_{\ell}) - \frac{1}{2} (\hat{\mu}_{k} + \hat{\mu}_{\ell})^{T}(\hat{\mu}_{k} - \hat{\mu}_{\ell}) + \log \hat{\pi}_{k}/\hat{\pi}_{\ell} \\ &> 0 \,. \end{align*}\]That is, we classify $\mathbf{x}$ to class $k$ if

\[\mathbf{x^{*}}^{T} (\hat{\mu}_{k} - \hat{\mu}_{\ell}) > \frac{1}{2} (\hat{\mu}_{k} + \hat{\mu}_{\ell})^{T}(\hat{\mu}_{k} - \hat{\mu}_{\ell}) - \log \hat{\pi}_{k}/\hat{\pi}_{\ell} \,.\]The derived allocation rule reveals the working of LDA. The left-hand side of the equation is the length of the orthogonal projection of \(\mathbf{x^{*}}\) onto the line segment joining the two class means. The right-hand side is the location of the center of the segment corrected by class prior probabilities. Essentially, LDA classifies the data to the closest class mean. We make two observations here.

- The decision point deviates from the middle point when the class prior probabilities are not the same, i.e., the boundary is pushed toward the class with a smaller prior probability.

- Data are projected onto the space spanned by class means, e.g. \(\hat{\mu}_{k} - \hat{\mu}_{\ell}\). Distance comparisons are then done in that space.

Reduced-rank LDA

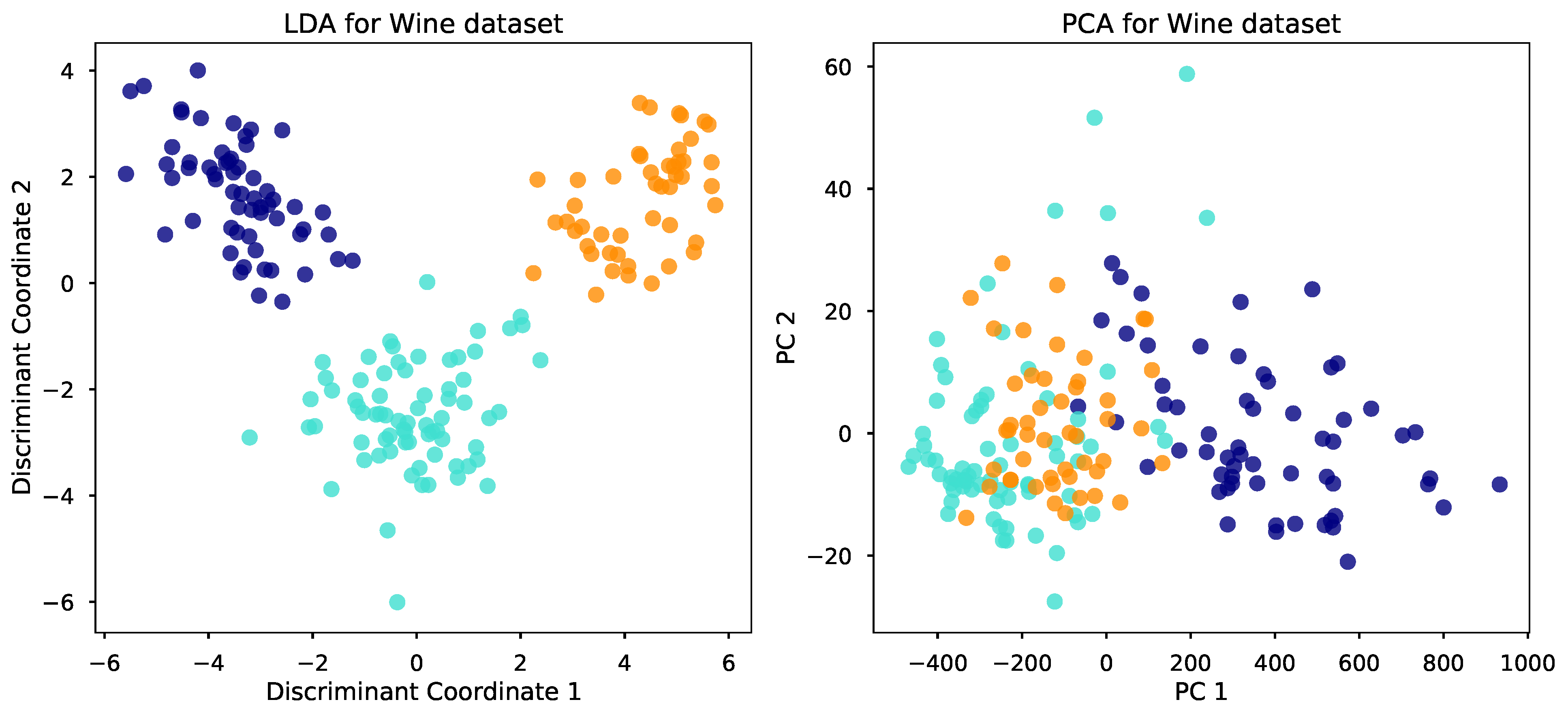

What I’ve just described is LDA for classification. LDA is also famous for its ability to find a small number of meaningful dimensions, allowing us to visualize and tackle high-dimensional problems. What do we mean by meaningful, and how does LDA find these dimensions? We will answer these questions shortly. First, take a look at the below plot. For a wine classification problem with three different types of wines and 13 input variables, the plot visualizes the data in two discriminant coordinates found by LDA. In this two-dimensional space, the classes can be well-separated. In comparison, the classes are not as clearly separated using the first two principal components found by PCA.

Click here for the script to generate the above plot.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn import datasets

from sklearn.discriminant_analysis import LinearDiscriminantAnalysis

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

%matplotlib inline

wine = datasets.load_wine()

X = wine.data

y = wine.target

target_names = wine.target_names

X_r_lda = LinearDiscriminantAnalysis(n_components=2).fit(X, y).transform(X)

X_r_pca = PCA(n_components=2).fit(X).transform(X)

with plt.style.context('seaborn-talk'):

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1,2,figsize=[15,6])

colors = ['navy', 'turquoise', 'darkorange']

for color, i, target_name in zip(colors, [0, 1, 2], target_names):

axes[0].scatter(X_r_lda[y == i, 0], X_r_lda[y == i, 1], alpha=.8, label=target_name, color=color)

axes[1].scatter(X_r_pca[y == i, 0], X_r_pca[y == i, 1], alpha=.8, label=target_name, color=color)

axes[0].title.set_text('LDA for Wine dataset')

axes[1].title.set_text('PCA for Wine dataset')

axes[0].set_xlabel('Discriminant Coordinate 1')

axes[0].set_ylabel('Discriminant Coordinate 2')

axes[1].set_xlabel('PC 1')

axes[1].set_ylabel('PC 2')

Dimension reduction is inherent in LDA

In the above wine example, a 13-dimensional problem is visualized in a 2d space. Why is this possible? This is possible because there’s an inherent dimension reduction in LDA. We have observed from the previous section that LDA makes distance comparison in the space spanned by different class means. Two distinct points lie on a 1d line; three distinct points lie on a 2d plane. Similarly, $K$ class means lie on a hyperplane with dimension at most $(K-1)$. In particular, the subspace spanned by the means is

\[H_{K-1}=\mu_{1} \oplus \operatorname{span}\left\{\mu_{i}-\mu_{1}, 2 \leq i \leq K\right\} \,.\]When making distance comparison in this space, distances orthogonal to this subspace would add no information since they contribute equally for each class. Hence, by restricting distance comparisons to this subspace only would not lose any information useful for LDA classification. That means, we can safely transform our task from a $p$-dimensional problem to a $(K-1)$-dimensional problem by an orthogonal projection of the data onto this subspace. When $p \gg K$, this is a considerable drop in the number of dimensions. What if we want to reduce the dimension further from $p$ to $L$ where $K \gg L$, e.g. two dimensional with $L = 2$? We can construct an $L$-dimensional subspace, $H_L$, from $H_{K-1}$, and this subspace is optimal, in some sense, for LDA classification.

What would be the optimal subspace?

Fisher proposes that the subspace $H_L$ is optimal when the class means of sphered data have maximum separation in this subspace in terms of variance. Following this definition, optimal subspace coordinates are simply found by doing PCA on sphered class means, since PCA finds the direction of maximal variance. The computation steps are summarized below:

-

Find class mean matrix, $\mathbf{M}_{(K\times p)}$, and pooled var-cov, \(\mathbf{W}_{(p\times p)}\), where

\[\begin{align} \mathbf{W} = \sum_{k=1}^{K} \sum_{g_i = k} (\mathbf{x}_i - \hat{\mu}_k)(\mathbf{x}_i - \hat{\mu}_k)^T \,. \label{within_w} \end{align}\] - Sphere the means: $\mathbf{M}^* = \mathbf{M} \mathbf{W}^{-\frac{1}{2}}$, using eigen-decomposition of $\mathbf{W}$.

-

Compute \(\mathbf{B}^* = \operatorname{cov}(\mathbf{M}^*)\), the between-class covariance of sphered class means by

\[\mathbf{B}^* = \sum_{k=1}^{K} (\hat{\mathbf{\mu}}^*_k - \hat{\mathbf{\mu}}^*)(\hat{\mathbf{\mu}}^*_k - \hat{\mathbf{\mu}}^*)^T \,.\] - PCA: Obtain $L$ eigenvectors \((\mathbf{v}^*_\ell)\) in \(\mathbf{V}^*\) of \(\mathbf{B}^* = \mathbf{V}^* \mathbf{D_B} \mathbf{V^*}^T\) cooresponding to the $L$ largest eigenvalues. These define the coordinates of the optimal subspace.

- Obtain $L$ new (discriminant) variables $Z_\ell = (\mathbf{W}^{-\frac{1}{2}} \mathbf{v}^*_\ell)^T X$, for $\ell = 1, \dots, L$.

Through this procedure, we reduce our data from \(\mathbf{X}_{(N \times p)}\) to \(\mathbf{Z}_{(N \times L)}\) and dimension from $p$ to $L$. Discriminant coordinate 1 and 2 in the previous wine plot are found by setting $L = 2$. Repeating the previous LDA procedures for classification using the new data, $\mathbf{Z}$, is called the reduced-rank LDA.

Fisher’s LDA

If the derivation of the previous reduced-rank LDA looks very different to what you’ve known before, you are not alone! Here comes the revelation. Fisher derived the computation steps according to his optimality definition in a different way1. His steps of performing the reduced-rank LDA would later be known as the Fisher’s discriminant analysis.

Fisher does not make any assumptions about the distribution of the data. Instead, he tries to find a “sensible” rule so that the classification task becomes easier. In particular, Fisher finds a linear combination of the original data, \(Z = \mathbf{a}^T X\), where the between-class variance, $\mathbf{B} = \operatorname{cov}(\mathbf{M})$, is maximized relative to the within-class variance, $\mathbf{W}$, as defined in (\ref{within_w}).

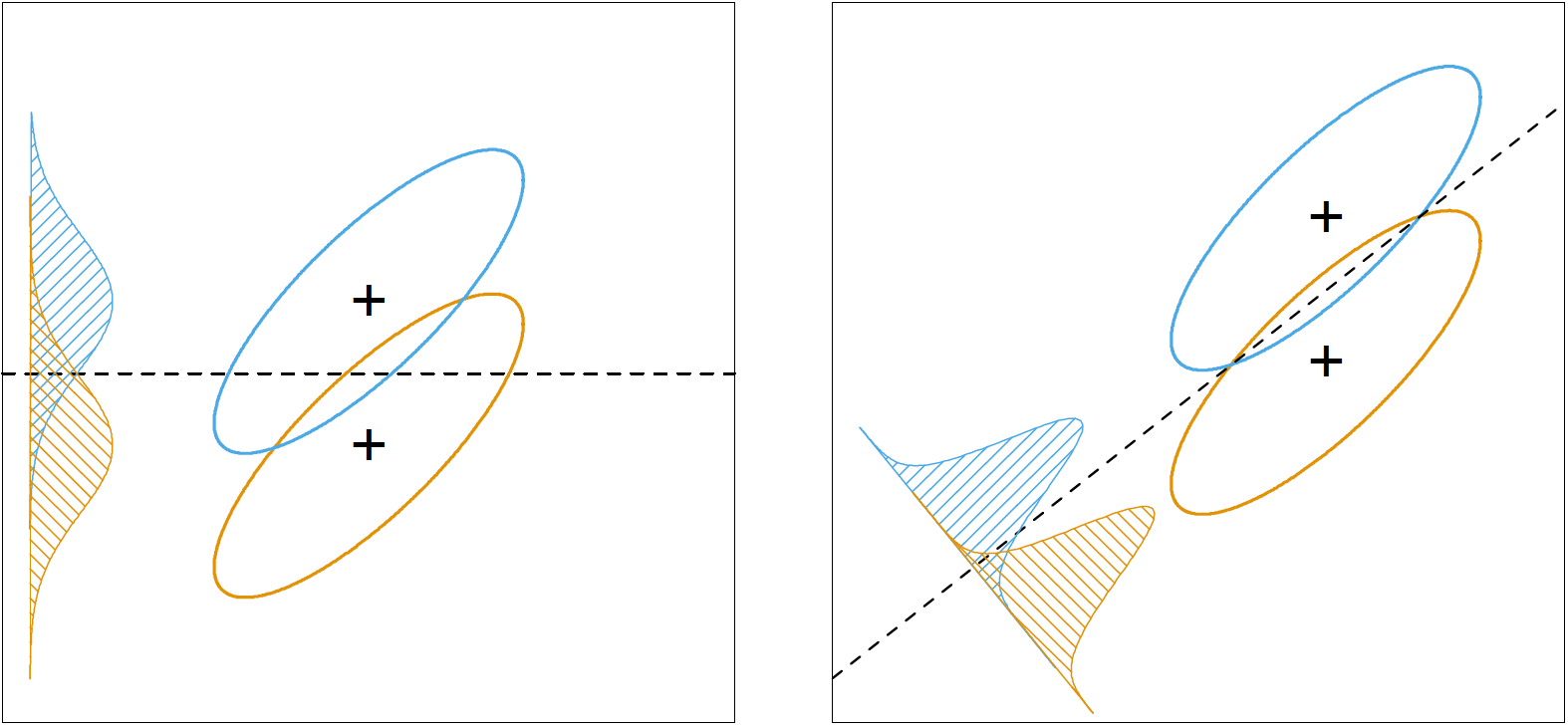

The below plot, taken from ESL2, shows why this rule makes intuitive sense. The rule sets out to find a direction, $\mathbf{a}$, where, after projecting the data onto that direction, class means have maximum separation between them, and each class has minimum variance within them. The projection direction found under this rule, shown in the right plot, makes classification much easier.

Finding the direction: Fisher’s way

Using Fisher’s sensible rule, finding the optimal projection direction(s) amounts to solving an optimization problem: \(\begin{align} \max_{\mathbf{a}} \frac{\mathbf{a}^{T} \mathbf{B} \mathbf{a}}{\mathbf{a}^{T} \mathbf{W} \mathbf{a}} \,. \end{align}\) Recall that we want to find a direction where the between-class variance is maximized (the numerator) and the within-class variance is minimized (the denominator). This can be recasted as a generalized eigenvalue problem.

The problem is equivalent to \(\begin{align} \label{eqn_g_eigen} \max_{\mathbf{a}} {}&{} \mathbf{a}^{T} \mathbf{B} \mathbf{a} \,,\\ \text{s.t. } &{} \mathbf{a}^{T} \mathbf{W} \mathbf{a} = 1 \,, \nonumber \end{align}\)

since the scaling of $\mathbf{a}$ does not affect the solution.

Let $\mathbf{W}^{\frac12}$ be the symmetric square root of $\mathbf{W}$, and $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{W}^{\frac12} \mathbf{a}$. We can rewrite the problem (\ref{eqn_g_eigen}) as

\[\begin{align} \label{eqn_g_eigen_1} \max_{\mathbf{y}} {}&{} \mathbf{y}^{T} \mathbf{W}^{-\frac12} \mathbf{B} \mathbf{W}^{-\frac12} \mathbf{y} \,,\\ \text{s.t } &{} \mathbf{y}^{T} \mathbf{y} = 1 \,. \nonumber \end{align}\]Since $\mathbf{W}^{-\frac12} \mathbf{B} \mathbf{W}^{-\frac12}$ is symmetric, we can find the spectral decomposition of it as

\[\begin{align} \mathbf{W}^{-\frac12} \mathbf{B} \mathbf{W}^{-\frac12} = \mathbf{\Gamma} \mathbf{\Lambda} \mathbf{\Gamma}^T \,. \label{eqn_fisher_eigen} \end{align}\]Let $\mathbf{z} = \mathbf{\Gamma}^T \mathbf{y}$. So $\mathbf{z}^T \mathbf{z} = \mathbf{y}^T \mathbf{\Gamma} \mathbf{\Gamma}^T \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{y}^T \mathbf{y}$, and

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{y}^{T} \mathbf{W}^{-\frac12} \mathbf{B} \mathbf{W}^{-\frac12} \mathbf{y} &= \mathbf{y}^{T} \mathbf{\Gamma} \mathbf{\Lambda} \mathbf{\Gamma}^T \mathbf{y} \\ &= \mathbf{z}^T \mathbf{\Lambda} \mathbf{z} \,. \end{align*}\]Problem (\ref{eqn_g_eigen_1}) can then be written as

\[\begin{align} \label{eqn_g_eigen_2} \max_{\mathbf{z}} {}&{} \mathbf{z}^T \mathbf{\Lambda} \mathbf{z} = \sum_i \lambda_i z_i^2 \,,\\ \text{s.t } &{} \mathbf{z}^{T} \mathbf{z} = 1 \,. \nonumber \end{align}\]If the eigenvalues are written in descending order, then

\[\begin{align*} \max_{\mathbf{z}} \sum_i \lambda_i z_i^2 &\le \lambda_1 \sum_i z_i^2 \,,\\ &= \lambda_1 \,, \end{align*}\]and the upper bound is attained at $\mathbf{z} = (1,0,0,\dots,0)^T$. Since $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{\Gamma} \mathbf{z}$, the solution is \(\mathbf{y} = \pmb \gamma_{(1)}\), the eigenvector corresponding to the largest eigenvalue in (\ref{eqn_fisher_eigen}). Since $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{W}^{\frac12} \mathbf{a}$, the optimal projection direction is \(\mathbf{a} = \mathbf{W}^{-\frac12} \pmb \gamma_{(1)}\).

Theorem A.6.2 from MA3: For \(\mathbf{A}_(n \times p)\) and $\mathbf{B}_(p \times n)$, the non-zero eigenvalues of $\mathbf{AB}$ and $\mathbf{BA}$ are the same and have the same multiplicity. If $\mathbf{x}$ is a non-trivial eigenvector of $\mathbf{AB}$ for an eigenvalue $\lambda \neq 0$, then $\mathbf{y}=\mathbf{Bx}$ is a non-trivial eigenvector of $\mathbf{BA}$.

Since \(\pmb \gamma_{(1)}\) is an eigenvector of $\mathbf{W}^{-\frac12} \mathbf{B} \mathbf{W}^{-\frac12}$, then, $\mathbf{W}^{-\frac12} \pmb \gamma_{(1)}$ is also the eigenvector of $\mathbf{W}^{-\frac12} \mathbf{W}^{-\frac12} \mathbf{B} = \mathbf{W}^{-1} \mathbf{B}$, using Theorem A.6.2.

In summary, optimal subspace coordinates, also known as discriminant coordinates, are obtained from the eigenvectors \(\mathbf{a}_\ell\) of \(\mathbf{W}^{-1}\mathbf{B}\), for \(\ell = 1, ... , \min\{p,K-1\}\). It can be shown that the \(\mathbf{a}_\ell\)s obtained are the same as \(\mathbf{W}^{-\frac{1}{2}} \mathbf{v}^*_\ell\)s obtained in the reduced-rank LDA formulation.

Surprisingly, Fisher arrives at this formulation without any Gaussian assumption on the population, unlike the reduced-rank LDA formulation. The hope is that, with this sensible rule, LDA would perform well even when the data do not follow exactly the Gaussian distribution.

Handwritten digits problem

Here’s an example to show the visualization and classification ability of Fisher’s LDA, or simply LDA. We need to recognize ten different digits, i.e., 0 to 9, using 64 variables (pixel values from images). The dataset is taken from here.

First, we can visualize the training images and they look like these:

Click here for the script.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn import datasets, svm, metrics

from sklearn.discriminant_analysis import LinearDiscriminantAnalysis

%matplotlib inline

digits = datasets.load_digits()

images_and_labels = list(zip(digits.images, digits.target))

for index, (image, label) in enumerate(images_and_labels[:4]):

plt.subplot(2, 4, index + 1)

plt.axis('off')

plt.imshow(image, cmap=plt.cm.gray_r, interpolation='nearest')

plt.title('Training: %i' % label)

plt.tight_layout()

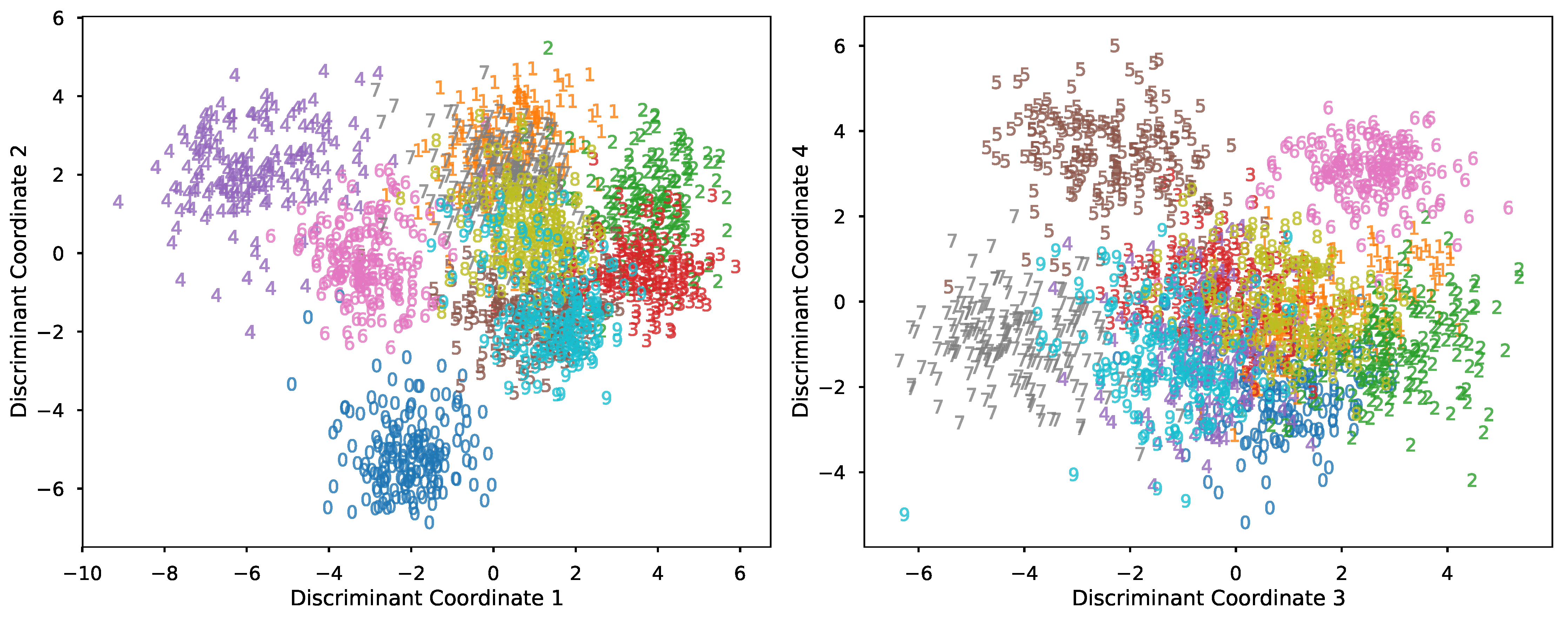

Next, we train an LDA classifier on the first half of the data. Solving the generalized eigenvalue problem mentioned previously gives us a list of optimal projection directions. In this problem, we keep the top 4 coordinates, and the transformed data are shown below.

Click here for the script.

X = digits.data

y = digits.target

target_names = digits.target_names

# Create a classifier: a Fisher's LDA classifier

lda = LinearDiscriminantAnalysis(n_components=4, solver='eigen', shrinkage=0.1)

# Train lda on the first half of the digits

lda = lda.fit(X[:n_samples // 2], y[:n_samples // 2])

X_r_lda = lda.transform(X)

# Visualize transformed data on learnt discriminant coordinates

with plt.style.context('seaborn-talk'):

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1,2,figsize=[13,6])

for i, target_name in zip([0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9], target_names):

axes[0].scatter(X_r_lda[y == i, 0], X_r_lda[y == i, 1], alpha=.8,

label=target_name, marker='$%.f$'%i)

axes[1].scatter(X_r_lda[y == i, 2], X_r_lda[y == i, 3], alpha=.8,

label=target_name, marker='$%.f$'%i)

axes[0].set_xlabel('Discriminant Coordinate 1')

axes[0].set_ylabel('Discriminant Coordinate 2')

axes[1].set_xlabel('Discriminant Coordinate 3')

axes[1].set_ylabel('Discriminant Coordinate 4')

plt.tight_layout()

The above plot allows us to interpret the trained LDA classifier. For example, coordinate 1 helps to contrast 4’s and 2/3’s while coordinate 2 contrasts 0’s and 1’s. Subsequently, coordinate 3 and 4 help to discriminate digits not well-separated in coordinate 1 and 2. We test the trained classifier using the other half of the dataset. The report below summarizes the result.

| precision | recall | f1-score | support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 88 |

| 1 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 91 |

| 2 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 86 |

| 3 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 91 |

| 4 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 92 |

| 5 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 91 |

| 6 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 91 |

| 7 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 89 |

| 8 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 88 |

| 9 | 0.77 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 92 |

| avg / total | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 899 |

Click here for the script.

n_samples = len(X)

# Predict the value of the digit on the second half:

expected = y[n_samples // 2:]

predicted = lda.predict(X[n_samples // 2:])

report = metrics.classification_report(expected, predicted)

print("Classification report:\n%s" % (report))

The highest precision is 99%, and the lowest is 77%, a decent result knowing that the method was proposed some 70 years ago. Besides, we have not done anything to make the procedure better for this specific problem. For example, there is collinearity in the input variables, and the shrinkage parameter might not be optimal.

Summary of LDA

Here I summarize the virtues and shortcomings of LDA.

Virtues of LDA:

- Simple prototype classifier: Distance to the class mean is used, it’s simple to interpret.

- Decision boundary is linear: It’s simple to implement and the classification is robust.

- Dimension reduction: It provides informative low-dimensional view on the data, which is both useful for visualization and feature engineering.

Shortcomings of LDA:

- Linear decision boundaries may not adequately separate the classes. Support for more general boundaries is desired.

- In a high-dimensional setting, LDA uses too many parameters. A regularized version of LDA is desired.

- Support for more complex prototype classification is desired.

In the next article, flexible, penalized, and mixture discriminant analysis will be introduced to address each of the three shortcomings of LDA. With these generalizations, LDA can take on much more difficult and complex problems.

References

-

Fisher, R. A. (1936). The Use Of Multiple Measurements In Taxonomic Problems. Annals of eugenics, 7(2), 179-188. ↩

-

Friedman, J., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2001). The Elements Of Statistical Learning (Vol. 1, No. 10). New York: Springer series in statistics. ↩

-

Mardia, K. V., Kent, J. T., & Bibby, J. M. Multivariate Analysis. 1979. Probability and mathematical statistics. Academic Press Inc. ↩